- Home

- James Costall

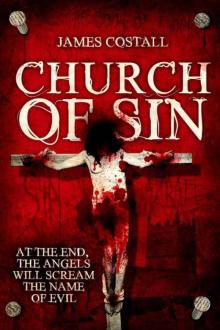

Church of Sin (The Ether Book 1) Page 2

Church of Sin (The Ether Book 1) Read online

Page 2

“This way, then,” he said and they followed him out together.

Chapter 4

As the others filed in to the Church of Saint Mary Our Virgin Jacob felt the change in the air. It wasn’t just the absence of the cold breeze on his face; it was the absence of everything. Like entering a vacuum, a space in which everything was temporarily suspended. He felt something stir within him, a feeling he had, like other feelings, forgotten. He felt the quickening of his heart and the sensation of blood pumping furiously through his veins. Blood charged with something ancient and cruel.

Like the others, he shuffled along the stone floor and down the central aisle. Took a pew to the left at the back. They sat in unison. A sad procession of puppets pulled and manipulated by invisible strings.

At the altar stood a man whose face was obscured by shadow. He wore a black robe that flowed around him like a demon’s wings, tied with a blood red cord around the waist. He stood motionless as Jacob and the others silently took their seats. Their eyes down. All of their eyes down on the floor.

Jacob’s head was spinning. There was a horrible churning in the pit of his stomach. He touched his face and ran his tongue carefully over his fingers. They tasted of salt. He studied them closely, looked at the contours on his skin that ran across his knuckles and the small mole on his thumb.

He didn’t recognise them.

He was there, standing over him. The man in the black robe. Hadn’t noticed him move from the altar. He couldn’t breathe. The fear was choking him. He looked up and into his eyes but there was nothing but black holes there. He thought his heart might burst from his rib cage.

“I know you feel it more than the others, Jacob,” he said. “You feel, yet you don’t feel. You are caught between worlds, Jacob. One foot in a real world and one in a dream world. They -” he swept his hand across towards the others – “they are already dead. You can’t save them. Empty cells waiting to be reused. That’s all. Nothing more.”

He moved his hand over the boy’s scruffy hair and down the back of his neck, across underneath his chin and over his face.

“It will be over soon,” he told him before striding to the front of the congregation and turning. The blade in his hand, long and curved, glinted in the sunlight shining through the stained glass windows. The sun was rising quickly. The night had all but retreated.

Jacob watched as he extended a hand and, although he couldn’t see the robed man’s eyes, he knew he was looking straight at him. And slowly, one by one, the heads of the others turned, their expressionless faces burning into him.

“In the name of Cronos, the Original Maker,” said the figure, “I choose you, Jacob, to make this Portal.”

Chapter 5

Alix had stayed up until the early hours of the morning absorbing everything she could about the Innsmouth Institute but nothing she had read had come close to suggesting that the hospital, or at least this part of it, remained in operation. She stayed close to Omotoso as he led them down seemingly endless, dimly lit corridors. Anwick’s lawyer followed a few paces behind, not wanting to make it appear as though he was actually with them, as if by doing so he somehow legitimized this place, but also making sure he could hear the conversation.

“How many patients do you have here?” she asked him as they rounded another corner.

“Sixteen.”

“Sixteen? That’s it?”

“Yep. Just one wing.”

“Why? Why just keep one wing open? And why keep this place secret?”

Omotoso glanced nervously over his shoulder. The lawyer had pricked up his ears and Alix, despite her desperation to understand, didn’t want him to know the truth either, whatever it was. She exchanged a look with Omotoso and decided not to push it.

There was a faint smell of disinfectant in the air but other than that nothing to suggest this was a working hospital. The walls were stained with some putrid yellow substance. The floor hadn’t been swept in years. There were no light fittings, just naked bulbs hanging perilously from the high ceiling, which was cluttered with uncovered pipes and wires and ventilation shafts. In places, the plaster had come away from the walls to reveal the flaking brickwork underneath.

Hardly an atmosphere that promoted healing, if indeed that was the idea.

Here, the boundary between hospital and prison was somewhat blurred.

She thought back to the blog entries she had read.

Innsmouth, lunatic asylum. Built in the early part of the nineteenth century, the complex expands over a four acre site. The Victorian utilitarianists constructed the Innsmouth Institute with the new belief that insanity could be cured. They had no concept or understanding of the complexity of mental illness and its different and varying forms. Abnormalities of the brain were there to be isolated and extracted using crude and often brutal techniques. In any event, incarcerating lunatics was expensive. Curing them was cheap. That paradigm had been all but extinguished by the end of the 70s. Asylums like Innsmouth are relics of a forgotten and dark age. The rise of institutional psychiatry has spawned a new era for the treatment of mental illness. Hospitals have replaced institutions. Drugs and therapy have replaced brutality and restraint. White walls and disinfectant have replaced stone and leather padded cells.

This place was a relic of a forgotten age. Why bother to fund it in secret?

“What sort of patients do you have?” Alix asked, trying to find a way to ask questions without putting Omotoso in a difficult position, although, frankly, she wasn’t convinced about the ethics of even working in a place like this. She was only really being tactful to spite the lawyer.

“The kind that don’t fit in with the normal system,” he replied.

“So you just go right ahead and take these folk outside the system and hide them from the world,” said the lawyer. He whistled as if to emphasise the absurdity of everything. “That makes you part of a serious violation to human rights, my friend.”

“It makes me a guy doing a job,” he replied.

Alix didn’t like it, but she had to admit to herself that the lawyer might have a point.

“So what happens when these guys’ families come to visit? Do they have to sign the Official Secrets Act too?” The lawyer again.

Omotoso stopped at another heavy door and fumbled around for his keys.

“The kind of patients we have here, mister, they don’t have people who want to come and visit them.” Alix nodded. She liked the way he talked. Everything he said was numbed with a mixture of sincerity and sadness.

The door creaked open and they followed him through to another corridor. Alix had lost track of how far they had come. She looked back anxiously but there was no way of telling how to get back to the entrance if she needed to. No friendly signs pointing to reception, or brightly coloured vending machines dispensing cans of coke, or little green bottles of disinfectant. Nothing.

“How are you funded?” asked the lawyer. “I will be pissed to the max if my tax money pays for this illegal joint.”

“We manage our own budget,” said Omotoso curtly.

“I mean look at this place! It’s a shit hole. I’ve seen cleaner public toilets in Soho.”

Alix wondered how many public toilets the lawyer had seen in Soho. Quite a few she imagined.

“I wish I’d never signed that damned paper.”

Alix looked at the lawyer sideways. He was out of his depth. If he knew anything about what he was into he would know that signing the Official Secrets Act was irrelevant. The Act was law. People given access to government secrets were bound by the terms of the Act whether they signed it or not. Signing was just to bring to their attention the penal consequences of failing to adhere to its terms. Alix felt a little better knowing that she wasn’t, perhaps, the most naive out of the three of them.

The corridor had widened and for the first time Alix could see out of the windows into a snow covered yard about the size of a football pitch surrounded by a twelve foot high fence crowned with b

arbed wire. Behind that, the looming wall she assumed to be outer perimeter complete with unmanned watch towers. The yard was deserted, except that there were tracks across the snow from the one end to the other. Freshly made from what she could see.

In this corridor, there was a faint noise bleeding through the walls on the opposite side to the windows. She wasn’t sure initially what it was. At first it sounded mechanical but, after a while, she recognised it. The unmistakable noise of a man in pain; the sorrowful moaning suppressed them all into silence, even the lawyer. Alix shivered.

“Tell me about Anwick,” she said to Omotoso, breaking the silence.

Omotoso sighed before saying, “complex, like the rest of ‘em. I need a lot more time to get to the bottom of him. He communicates intermittently through what I think is an alternative personality who calls himself Azrael.”

“Dissociative identity disorder,” Alix suggested.

“The definition of DID requires there to be two or more personality states that recurrently assume control of the mind. But I’ve only met Azrael. So technically that only makes one. Just not the right one.”

“Could be that the alternative personality is dominating in the early stages shortly after the trigger event.”

“Could be. Not enough time to do a proper screening yet. Have you ever read DSM-5?”

Alix shook her head, although she knew he was referring to the criteria for the diagnosis of DID set out in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders but what the Manual said was well beyond her expertise.

“Just what are you two eggheads babbling about?” said the lawyer impatiently. His stumpy legs meant he had to sort of skip on every third or fourth step to keep up with Omotoso’s long strides.

“Your client’s been through considerable trauma,” Alix explained. “But the mind is an incredible survivor. In rare cases, the mind recognises that it can’t deal directly with the trauma it’s experienced and so an alternative personality is created to take control and to shield the real personality from further deterioration. Childhood sexual abuse is a typical trigger for the emergence of an alternative personality in adulthood but extreme psychological stress, such as that which your client has endured, could also produce the same effect.”

“I guess that would help an insanity plea,” said the lawyer slyly.

“Not really. If there is an alternative personality then it came after what happened to your client,” said Omotoso.

They turned a final corridor which opened out into a larger room with cell doors (there was no better way to describe them) on the right and glass looking out onto the snowy yard on the left. Omotoso led them to the end door next to which was hung a chalk board.

Prof. Eugene Anwick

16

The lock snapped back and Alix found herself in a small room and another door directly ahead. The walls were brick, the floor concrete. In the corner there was a small desk behind which Alix recognised the pale man who had introduced himself earlier as Ned. He was sat hunched over a laptop and didn’t look up when they came in. Other than that, the room was bare.

Alix heard the clank of the door close behind her.

“Doctor Omotoso,” said the lawyer, “this place is completely unethical and I will not participate anymore in this abomination! I demand that my client be transferred immediately to a psychiatric hospital where he can be placed under the care of real professionals, not amateurs like you and your pet over there!”

His face had become even redder and he had developed a nasty rash around his neck. She backed away in the corner hoping not to become involved.

“Listen, mister, calm down,” said Omotoso. “We’re guys doing jobs, like I said. You want to make noise when your otta’ here and shout and whatnot then fine, be my guest. They’ll stick you behind bars quicker than you can tear up that little piece of paper that you signed, though.”

“I will not be spoken to like a school boy, Doctor!” He was close to shouting and Alix felt compelled to at least try and lend a hand. He was right about the only-doing-a-job bit she supposed and that probably warranted the benefit of the doubt.

“Listen, I have a patient to assess. Can this wait?”

“Oh, I see, you have a patient to see? Well that’s great. Don’t you care that your patient is being held in this unhygienic, backwater prison?”

“Yes, I do care. But these people can’t do anything about it. Just like you can’t. So can we just get on with what we’re here to do?”

He seemed to calm down a bit and resorted to huffing a lot and scribbling in his notepad. Omotoso looked embarrassed and Alix felt he wanted to tell her something but he couldn’t speak openly. Ned seemed unimpressed by the whole exchange, like it didn’t even matter to him. But Alix noticed him watching her out of the corner of his eye. She felt very anxious in this room full of testosterone.

“Can I see the professor now?” she asked, turning to Omotoso.

“Of course.”

She stepped forward to a door on the other side of the room. It seemed the same as every other door except this one was controlled by a key pad to the right. Omotoso paused before entering the code.

“Just stay cool in there, okay?” he said to her.

“What do you mean?”

He hesitated before responding.

“There’s a yellow line drawn across the floor of the room. Stay this side of the line. That’s the only rule.”

She looked at him. His expression was quite serious. She turned back to the lawyer.

“Aren’t you coming in with me?”

He shuffled his feet a little before saying, “I’m sure I can monitor your conversation with the professor from out here, thank you.”

“You drove all the way out here, banged on about human rights and how poorly your client is being kept but you won’t talk to him?”

“I’m perfectly happy out here, thank you.”

She shrugged her shoulders, Omotoso hit the numbers, and she was in.

Chapter 6

Alix stepped forward gingerly. She was inside a room similar in size to the one she had come from, no larger than twenty yards either way. White washed brick walls. Windowless. Airless. This was no treatment room. There was no bed, no curtains, no cabinets, sinks, pin boards, plants. Nothing. This wasn’t a hospital. It wasn’t even a prison by modern standards.

The yellow line Omotoso had mentioned dissected the room about half way giving her about ten feet of movement. Other than that, and the figure sat hunched over himself in the far corner, the room was nothing more than an empty box.

She couldn’t see Anwick’s face. Just a mass of wiry hair, as white as the brickwork, falling about him and hiding his features. To her horror, she saw he was cocooned tightly in a pale orange straightjacket, arms bent round his back and secured with various clasps and buckles like a snared fly is woven into a spider’s web.

“Jesus,” she murmured. They’d stopped using straightjackets decades ago. “What is this place?”

She felt her heart rise up through her chest and lodge itself in her throat. There was a vulgar smell of stale urine in the air. She covered her mouth to try and stop herself from gagging. She took a moment to settle herself before taking another step forward and addressing the hunched figure.

“Hello,” she said. “I’m Doctor Franchot. I’m a psychologist. You’re Professor Anwick?”

The heap in the corner didn’t move, other than as a result of his laboured breathing. There was something so very feral about him, and more animal than man at that. Alix took another step forward and lowered to her knees. She didn’t want to appear threatening in any way, although she felt sure that if anyone was going to feel threatened in this room it was more likely to be her.

“Professor? Can you hear me?”

There was no response and she suddenly felt very inept. This man was suffering from a complex mental disorder. She wasn’t trained to deal with him. She stole a look at the security camera over

her shoulder. Surely any minute now Omotoso and the lawyer would stride in and take over. It was obvious she didn’t know what she was doing. She swallowed hard but her mouth was dry. The feeling of nausea had returned.

An assessment, Baron had told her. Christ, this was her first assignment in her new role. Not exactly what she had been employed to do, or so she thought. But good experience, Baron had said. Had he any idea what he had set her up for?

“Professor Anwick? Eugene?” You’d have to be an idiot not to detect the tremor in her voice, she thought; see the beads of sweat begin to form on her brow, the uncertain way she held her hands on her knees for support, her arms trembling slightly. She felt a fraud, a fraud on the verge of detection. What had Omotoso said about the alternative personality? His words seemed to make no sense now she thought about them. Shit, had she even been listening?

Azrael. That was it.

“Azrael?”

Anwick looked up so suddenly she thought her heart might burst from her ribcage. She stared at him. His face was plain but with crooked, angular features. They looked like they had been drawn by a child. His skin was an unhealthy yellow colour, his lips thin and cracked. Eyes were no more than slits of black etched into an emaciated facade but she could see they were full of anger, resentment and hunger. Professor Anwick had the appearance of one who had suffered the agonies of Hell itself only to have been regurgitated and coughed up kicking and screaming back into the world.

“Azrael,” Alix said again quietly. Now that she had Anwick’s attention she stood up slowly and took another step forward.

“What do you know about Azrael, child?” Alix had expected Anwick’s voice to match his face: deep and textured. But it couldn’t have been more different. She had expected the rasp of a demon but instead what she heard would have been more likely to have belonged to a young girl: soft, lyrical, benign.

Church of Sin (The Ether Book 1)

Church of Sin (The Ether Book 1)